In June 2014 the Houghton Library at Harvard University announced that its copy of Des destinées de l’âme, a meditation on the soul by the French novelist and poet Arsène Houssaye dating from the mid-1880s, had been subjected to mass spectrometry testing and was “without a doubt bound in human skin.” The book had been presented to the library in 1934 and was one of three in Harvard’s libraries that had recently been tested. The other two turned out to be sheepskin. “While the unusual and grotesque provenance have made the book a popular object of curiosity, particularly to undergraduates,” the Houghton’s press release concluded, “it serves as a reminder that such practices were at one time considered acceptable.”

Conserving and displaying the book in the twenty-first century, however, was another matter. Whose skin was used, and what was the story behind it? It turned out that the author had presented a copy of his book to Ludovic Bouland, his friend and a prominent Strasbourg doctor who had in his private collection a section of skin from a woman’s back. Bouland knew that Houssaye had written the book while grieving his wife’s death and felt that this was an appropriate binding for it—“a book on the human soul merits that it be given human clothing.” He included a note stating that “this book is bound in human skin parchment on which no ornament has been stamped to preserve its elegance.” But Bouland’s gesture, however compassionate in intent toward Houssaye, concealed an unedifying history: the skin had been removed without consent from a mentally ill patient who had died in an asylum, her body left unclaimed. The library’s announcement, which made no mention of how the skin had been sourced, provoked outrage. “The binding is a macabre disgrace from a time when the human dignity of the mentally ill and others was readily discounted,” one commenter responded on the university website. “Got any vintage WWII lampshades, Harvard?” Another advised: “Get rid of it quickly!”

Megan Rosenbloom’s first encounter with a book bound in human skin—“anthropodermic bibliopegy” is the technical term—took place at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia, a medical history collection renowned for its striking and in some cases grotesque anatomical curiosities, which she frequented with “a mix of eager fascination and quiet contemplation of mortality.” As she embarked on a career as a medical librarian, with its twin specialisms in medical history and rare books, her fascination with these mysterious and highly charged objects grew. Anthropodermic books, she discovered, have a long-established history, though not the one that might be assumed from their appearances in urban legends and popular fiction.

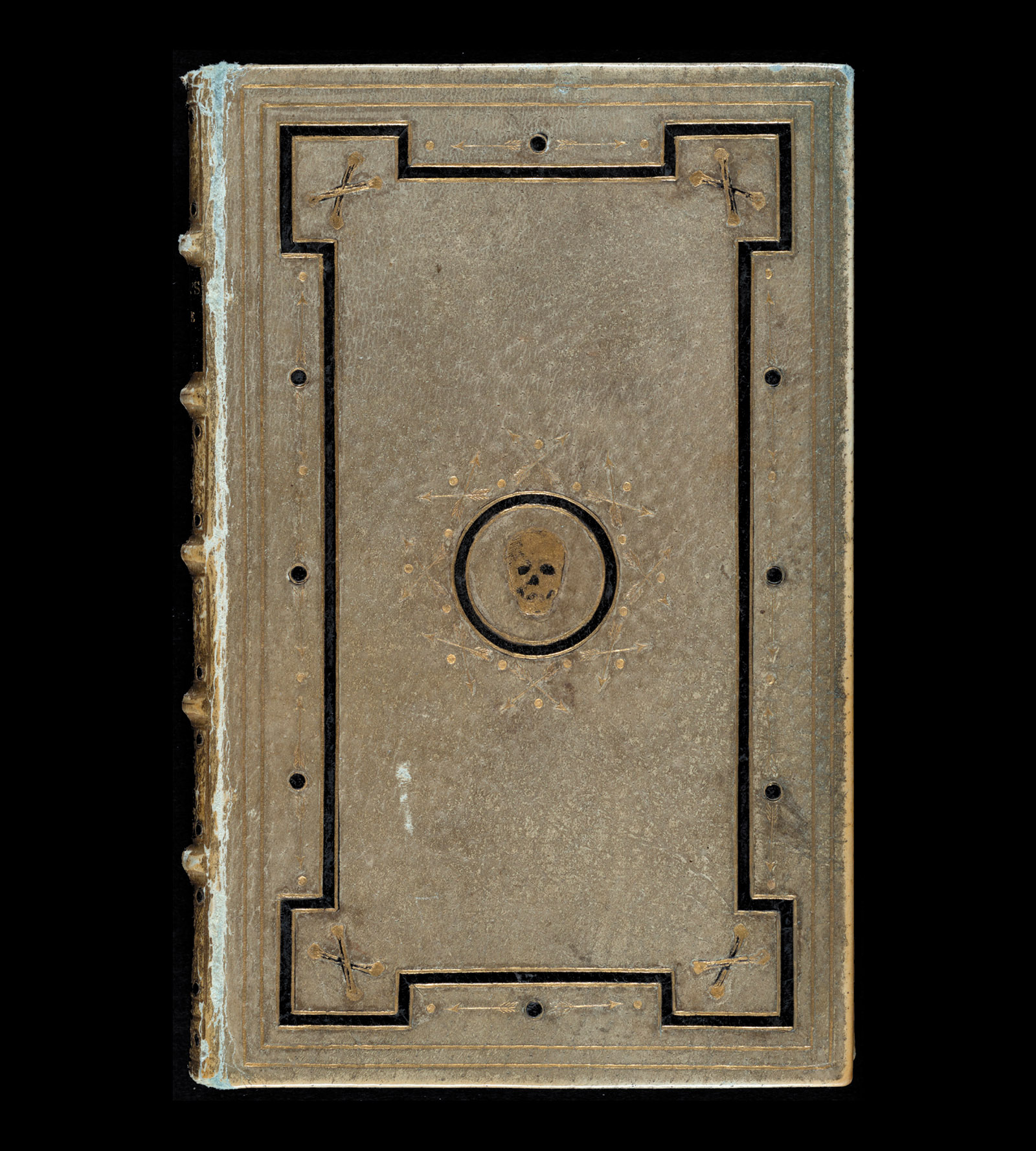

Although they have become a familiar trope in horror movies such as The Evil Dead, they are not medieval grimoires or occult tomes. Neither are they mementos of serial killers, nor grisly products of the Nazi era: despite the oft-told tales of human-skin artifacts from Buchenwald concentration camp in particular, all the alleged books (and lampshades) tested thus far have turned out to be animal-hide fakes, produced for the ghoulish souvenir trade. Genuine examples are usually unremarkable in appearance, looking and feeling no different from other leather-bound books and rarely advertising themselves with inscriptions or gothic designs. The true story, which Rosenbloom recounts in Dark Archives, is less sensational and more ambiguous, though not without its monsters.

The first step in a history of anthropodermic books is addressing how one identifies the genuine article. There is an extensive literature on the subject—as far back as 1932 the bibliophile scholar Walter Hart Blumenthal published a survey, “Books Bound in Human Skin,” in the journal American Book Collector—but bibliophiles have often been uncritical in printing the legends rather than the facts. Dealers and collectors both stand to gain from the rarity and taboo value of any alleged human-skin book. They tend to be sold discreetly within this specialist community for prices that are not publicly disclosed but are high enough to encourage the widespread production of fakes. These are typically bound in calf or pigskin, which is the most similar in appearance to human skin. Some experts claim to be able to distinguish them by counting the pores or studying the depth of the follicles, but most agree that there are no reliable visual markers.

Together with two chemists and the curator of the Mütter Museum, Rosenbloom, a medical librarian at UCLA, has established the Anthropodermic Book Project, which tests tiny samples of leather or parchment bindings by peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF). The protein marker that identifies human skin is shared by other primates: gorillas, chimpanzees, and orangutans. In the case of ungulates (hooved mammals), there is a marker that helpfully distinguishes cow, sheep, and goat leather. (Other animal families, such as whales, are more varied and can be identified by species.) PMF works better on parchment—stretched and dried animal skin—than on leather, which is tanned to create a finished product more resistant to rot, moisture, and heat. Prior to modern industrial methods, tanning was a malodorous process that used animal dung and urine to break down fats and blood, making the protein marker of the original skin harder to identify.

Advertisement

The Anthropodermic Book Project’s list of confirmed human skin books, as of March 2020, runs to eighteen. (Thirty-one have been tested thus far, including thirteen that have been proven to be nonhuman.) Progress is slow. Dealers and private collectors often prefer to preserve the mystery rather than risk diminishing their book’s value with a negative result, and libraries have little appetite for the notoriety or public outcry a positive identification can invite. In 2008 Stanley Cushing, the curator of rare books at the Boston Athenaeum, agreed to promote the library by featuring an anthropodermic volume from its collection on the TV show Mysteries at the Museum. When the show ended up on Netflix, he decided the initiative had been all too successful. “You don’t really want to be known for whatever freakish thing you own,” he told Rosenbloom. “People come in on Halloween and want to see it. That’s not really who we are, please…”

There are around twenty more candidates for testing on Rosenbloom’s current list, which continues to expand. It’s only toward the end of the book that she visits Paris, where she discovers that Arsène Houssaye’s volume is part of a French tradition more flamboyant and probably more extensive than that of the Anglophone world. She sees photographs of books bound in skin with human nipples, and others with tattoos. “I was floored,” she writes; “never before had I seen any human skin books that were so obviously of human origin.” She had heard rumors—for example, about a scandalous anthropodermic copy of the Marquis de Sade’s Justine and Juliette—but had discounted them as decadent mythmaking.

Early in the book she tells us that “so little was known about these macabre objects; the only mentions of them in the academic literature are old and filled with more rumor and innuendo than confirmed fact.” It’s surprising that she doesn’t mention the project that has been running parallel to hers at the University of Paris-Nanterre, where in 2017 Jennifer Kerner assembled a bibliography of 136 alleged anthropodermic books. The majority are in private collections, and few have been tested; Kerner is in any case a little skeptical of PMF testing, especially of tanned leather, for which it has on occasion produced contradictory results. In her view, a secure identification requires full DNA fingerprinting from an interior sample, which is considerably more expensive and also more destructive, since it requires digging into the cover. Nonetheless, Kerner’s much longer list of plausible candidates tells a story that matches Rosenbloom’s in most respects, and in others extends it.

Paris seems to have been where the phenomenon took hold. One of the legends persistently recycled in anthropodermic histories is that during the French revolutionary terror in 1793–1794, bodies were taken from the guillotine to a human-skin tannery set up outside the city at a former royal castle, the Château de Meudon. Republican generals, it was said, paraded in human skin culottes, and guests at a revolutionary ball held in a cemetery were presented with anthropodermic copies of Thomas Paine’s The Rights of Man. The story was propagated through Catholic and Royalist sources and made its way into histories of bookbinding, where it is still repeated on occasion, though recent historians have found no evidence for it. Yet it points to a transformative moment in medical history, of which one consequence turned out to be the fashion for books bound in human skin.

In the revolutionary French republic, the medical profession became a significant arm of the state for the first time. Care of the sick, previously dispensed by church charities, was taken over by public hospitals, where junior doctors were taught anatomy by observing autopsies and dissecting deceased patients. As Michel Foucault wrote in The Birth of the Clinic (1963), this new generation of professionals was taught to observe pathological disorders dispassionately and developed a “medical gaze” in which the patient was reduced to an object of study. The age-old sanctity of the dead body was replaced with a secular and technical ethos that disconnected the cadaver as far as possible from the person it had been. Under this new regime, anatomical specimens, because of their educational value, became status symbols within the profession, most readily available to its senior and distinguished members.

Advertisement

In her survey of the US archives, Rosenbloom relates one of the few examples of anthropodermic bibliopegy in which the cadaver and the person can be reconnected by documentary evidence. In the late 1880s Dr. John Stockton Hough, a resident at the Philadelphia General Hospital, bound three of his favorite medical books on female health and reproduction in skin that he had removed from a patient’s thigh during an autopsy in 1869, before the rest of the body was consigned to a pauper’s grave. Handwritten notes in the copies state that the leather was tanned in 1869 by “J.S.H.” himself. References to its source as a patient named “Mary L—” allowed Beth Lander, a librarian at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, to match it in 2015 to Mary Lynch, a twenty-eight-year-old Irish widow who had died from tuberculosis at the hospital in January 1869.

Most confirmed anthropodermic books, such as Dr. Hough’s, were generated by this gruesome intersection of two nineteenth-century gentlemanly cultures: the medical profession and bibliophile collecting. Cadavers were available to doctors for experiment in unprecedented numbers, and it was also a golden age of bookbinding. Books were still commonly sold as text blocks, fastened by stitch and glue but without a cover. Collectors would have their copies custom bound in leather, often personalized by stamping or embossing and combining a selection of short texts or pamphlets into a unique volume.

Bibliophilia was common among doctors, a signifier of wealth and taste in an upwardly mobile profession. Hough was a well-known but not exceptional case: he traveled to Europe to buy antiquarian medical texts and was a member of New York’s Grolier Club, the first private bibliophile society in the United States. By 1880 his library was estimated at eight thousand books, and when Mary Lynch’s skin was used as bookbinding later in the decade, those three volumes would have been shelved inconspicuously among the yards of privately commissioned leather spines.

An early-nineteenth-century British vogue for human-skin binding, extending beyond the polite milieu of bibliophile doctors, is characterized by Rosenbloom as “murderabilia.” The public hangings of notorious murderers were typically followed by public autopsies—a posthumous humiliation—and on occasion by unseemly scrambles for souvenirs from the flayed corpse. In 1827, for instance, the British newspapers were transfixed by the case of William Corder, convicted of the “Red Barn Murder.” Corder had shot and stabbed his lover, burying her beneath the barn before fleeing rural Suffolk for a new life in London. After his execution, five thousand people lined up to view his body. The following day it was dissected and a galvanic battery attached to its limbs to observe the dead muscles contract. A death mask was made and sections of his skin removed. A piece of leather made from his scalp is still on display in Moyse’s Hall Museum in the Suffolk town of Bury St. Edmunds, alongside a copy of the trial transcript bound in his tanned skin.

The following year, the murders by the Edinburgh graverobbers William Burke and William Hare—the most sensational British crime of the era—marked the end of this vogue. Burke and Hare supplied cadavers to the leading Scottish anatomist Robert Knox for his hugely popular twice-daily anatomy lectures at the University of Edinburgh, until they were tried and convicted of murdering sixteen of the people whose bodies they had supplied. The public inquiry that followed led to the Anatomy Act of 1832, which created a legally regulated supply of bodies for study in medical schools and ended the practice of dissecting executed criminals. A book bound, allegedly, in William Burke’s skin is housed today in the Surgeons’ Hall Museum in Edinburgh. Unusually, it announces itself in gold-stamped letters—Burke’s Skin Pocket Book—with the date of execution inscribed on the back. It remains first on Rosenbloom’s wish list for PMF testing.

After the Anatomy Act, similar legal measures to regulate dissection were adopted in the US on a state-by-state basis. Their effect was to restrict the supply of human skin to doctors and surgeons, and anthropodermic books to the bibliophile members of those professions. In France, however, a more diverse market seems to have persisted as part of what Holbrook Jackson, in his classic study The Anatomy of Bibliomania (1950), dubbed “bibliopegic dandyism”: the pursuit of rare and exotic materials for book coverings. Collectors bound their prized volumes in Persian or Chinese silk, ivory, and skins, including those of pythons, sharks, crocodiles, walruses, monitor lizards—and, on occasion, people.

The twenty or so confirmed examples of human-skin-bound books in Jennifer Kerner’s bibliography are mostly works on sexual themes, ranging from medical tracts on perversion to erotic poetry, that circulated among collectors of illicit and pornographic material. Female skin seems to have been preferred, usually from the breasts or thighs and on occasion including nipples or tattoos as a flourish of decadence. Most of these books are in private collections, and testing is a no-win proposition for French dealers: if they are found to be genuine, they fall foul of a national law that prohibits the sale of human remains. Neither Rosenbloom nor Kerner gives examples of any prosecutions relating to human-skin book bindings that may have occurred. Rosenbloom’s team has, however, succeeded in establishing that an 1892 French edition of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Gold Bug, adorned with a skull emblem, is genuine human skin: Poe en peau humaine.

Kerner’s list extends into the early twentieth century, but neither she nor Rosenbloom has found any anthropodermic books from the postwar era. By the 1950s anatomical schools had become more tightly regulated, and the principle of medical consent, formulated in the Nuremberg Code, was enshrined in international law. Today human-skin artifacts occupy a gray area in law as well as ethics. Human remains are neither person nor property; they have no rights, but the legality of buying, selling, and owning them is questionable (as was further established in recent years with “Body Worlds,” the controversial touring exhibitions of “plastinated” cadavers, amid claims that they have included body parts from executed criminals). Laws on human remains mostly protect whole cadavers and skeletons but not artworks or objects that include human body parts modified “through the application of skill,” as British law puts it. The same distinction is frequently at the center of disputes over the repatriation of tribal artifacts from museums.

When Rosenbloom speaks to Simon Chaplin, at the time the director of the Wellcome Library in London—which was founded by the collector of medical objects Henry Wellcome and includes anthropodermic books and tattooed skin in its collections—he stresses the need to be “sensitive to the contexts of the acquisition, the history, and the current circumstance.” An anatomical specimen has been prepared, acquired, and used for teaching; human-skin books were created, collected, and traded for a variety of different reasons. Other curators are more dogmatic. Paul Needham, then the Scheide Librarian at Princeton, describes Harvard’s copy of Des destinées de l’âme uncompromisingly as “post-mortem rape,” an attack on a dead female body. A library’s duty of preservation, he argues, doesn’t extend to the binding of books: if these are abhorrent, they can legitimately be removed and destroyed.

As her narrative progresses, Rosenbloom considers her own motives more closely. The book begins as a quest for the fascinating and forbidden: the reader is invited to share the thrill of pursuit, and of the moment when the sinister and legendary provenance of a book is scientifically verified. But as the histories of these books unfold, the focus necessarily shifts from their creators and possessors to the lives of those who supplied the skin. It becomes impossible to ignore the dissonance between the rare, fabled, and costly items on display and the devaluing of human life they represent.

Rosenbloom identifies as “death-positive,” an advocate for openness about death and dying (and also as a lapsed Catholic, which frames her fascination with human relics and their sacred and aesthetic power). The challenge she faces is to satisfy her avowedly morbid curiosity while also doing justice to the stories of those who ended up as book covers. The most productive case history in this respect is that of George Walton, a notorious highwayman who died of tuberculosis in a Massachusetts state prison in 1837. During his final days, Walton requested that the attending physician posthumously remove a section of skin from his back; it was taken to a local tannery, and a bookbinder turned it into a gold-tooled leather book cover. The text it encloses is Walton’s own life story and confession of his crimes, which he dictated to a kindly prison warden who had assisted him in his conversion to Christianity. “Although he didn’t have his freedom,” Rosenbloom concludes, “Walton took power over what happened to his body in death.”

A PMF test on the book, now held in the Boston Athenaeum, enabled Rosenbloom to confirm that the binding was of human origin. She had suspected this, since its story was so distinctive. Kerner has it as one among at least eight cases of anthropodermic books made from voluntary donors, but it appears to be the only one that contains the subject’s own words. It complicates any universal judgment on anthropodermic books by asking a more specific question: Is it the practice of human-skin binding that should be seen as unethical or the erasure of agency on which it’s typically predicated?

Walton’s final gesture prompts Rosenbloom to consider the post-mortem fate of her own body. She would like to make her cadaver available for dissection, but the criteria for this are more stringent than organ donation, and the two are mutually exclusive: bodies donated for anatomical study must have all their organs intact. Donated organs save lives, while dissection benefits the living only indirectly. She joins a group of medical students to watch their first encounters with cadavers; once she recovers from the formaldehyde fumes, she is struck by how quickly the students develop the “medical gaze” required to approach a human body as a source of learning.

Another option is to preserve her tattoo, a handsome design adapted from a bookplate used by the Historical Medical Library of Philadelphia. It turns out there are organizations devoted to this purpose, including the Foundation for the Art and Science of Tattooing in Amsterdam, which offers a tanning and preservation service that strikes her as “the closest modern practice to historic anthropodermic bibliopegy.” During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, tattooed skin was preserved and traded by medical collectors, ethnographers, and criminologists in a market that overlapped with that for human-skin book bindings.

The most celebrated collection resides in the Science Museum archive in London: three hundred examples bought from a Parisian doctor by Henry Wellcome’s agent in 1929, who recorded them as “skins of sailors, soldiers, murderers and criminals of all nationalities.” Rosenbloom describes them mistakenly as “wet specimen tattoos floating in jars”; in fact, they’re dry-prepared skin sections, two of which were until recently pinned out on permanent display in Wellcome Collection’s galleries. Gemma Angel, a British scholar who has studied their history in detail, tells a parallel story in her published research of bodies dehumanized by medical collectors, but she points out that in the case of tattoos, the subjects can themselves be seen as collectors—of travel souvenirs or clandestine badges of membership—“ironically bound” to their posthumous purchasers “by their mutual engagement with the inscription.”

The irony persists today. As Rosenbloom discovers, a tattoo donated to the Amsterdam preservers becomes the property of their foundation, to be used for artistic and educational purposes as they see fit. Modern anthropodermy improves on its antecedents by being consensual and documented, but the legal questions remain murky: consent and contracts may not amount to legal force, and much depends on where your body ends up. Of course, volunteering one’s own body for preservation does little to resolve the tensions between morbid curiosity and bearing witness to historic injustice that are implicit in studying the subject. But it is still possible, if one chooses, to become an object of such studies oneself.