This article originally appeared in the July 2004 issue of Esquire. You can find every Esquire story ever published at Esquire Classic.

The coffee, he thinks. The coffee's a concern. Only one hundred single-serving pouches of instant were allotted for him on Expedition Six, stowed in the galley in a metal drawer with a black net stretched over its mouth to make sure the pouches wouldn't float away. But for all the care in the universe, it's been more than two months since the shuttle delivered him and his coffee to the International Space Station, and there aren't one hundred pouches in that drawer anymore.

Looking out his window at the orbital sunrise, Donald Pettit, the mission's science officer, finishes taking mental stock of the supply and decides, Jeez, this is the sort of morning coffee was made for. He puts on his glasses, pulls himself out of the sleeping bag that he's anchored to the wall, pushes his way out of his private quarters—about the size of a phone booth, in Destiny, the last link in the station's chain of modules—and finds his center of gravity. With it, he propels himself in clean, practiced movements, like a swimmer who's found his stroke, toward the other end of the station, a couple of modules and a little less than 150 feet away. There, his commander, Captain Kenneth Bowersox, and the Russian flight engineer, Nikolai Budarin, lie zipped away, still asleep. Pettit opens the metal drawer and takes out a pouch, a silver bag with powder packed hard into the bottom of it. He fills it with hot water that was once his breath and begins hunting for a straw.

Everything is always taken through a straw. Except that Pettit has learned to squeeze his coffee out of the straw in tiny, perfect spheres, which hang suspended in the weightlessness, waiting for him to bite them out of the air or, if he's feeling playful, to pinch them between chopsticks and pop them into his mouth. He does that because he can up here, and he can't down there. That's all the reason he's ever needed.

On this morning, though, he just finds a straw and a little Russian tvorog to eat and heads back to his sleeping bag. It's an easy Saturday, the first of February. There's some housecleaning to do—the crew's well-worn routine dictates that they'll spend this weekend unclogging filters, wiping down handrails with antiseptic solution, even mopping up the occasional coffee splatter, the tiny, perfect ones that got away. But there's no hurry. Time is the single thing they aren't running out of. They're still a month away from home.

Pettit takes a sip and watches the sun rise for the second time. It comes and goes every forty-five minutes, good for sixteen dawns and dusks a day. Even after ten weeks in space, it's the sort of thing that draws you close to the window. There are the vapor trails, too, laid on top of the United States each day like a quilt, New York to Los Angeles, Boston to San Francisco; they're Pettit's way of catching a glimpse of home even when it's shrouded in storms. But today the horizon is clear and the sun is bright, so bright that he won't notice the finger of white smoke in the wide Texas sky.

Each Saturday, at about two o'clock in the afternoon, Greenwich mean time—sailor's time, the official time zone of the station—there's a ground conference with Houston to plan the upcoming week. Usually, the voice coming out of the radio tells the crew what they already know, and they float around, puttering, keeping their ears half open for news or drama. This time is different. This time, the voice tells Expedition Six to stand by.

Inside Mission Control, where the space station's orbit is tracked on a giant screen at the front of the room and technicians sit behind consoles labeled ODIN, OSO, ECLSS, ROBO, and a dozen other things, a debate is unfolding. No one is sure how to tell the crew that Columbia, a shuttle that Bowersox has twice piloted, just came apart in the thin blue-green envelope beneath them. No one is sure how to tell them that seven friends—including Ilan Ramon, who only a few days earlier told Bowersox that he'd give his three children a hug for him, and Willie McCool, with whom Pettit had been playing e-mail chess—are probably gone, too.

Jefferson Howell, a retired marine lieutenant general and the plainspoken director of the Johnson Space Center, ends the debate when he sits down at the radio, considers his words, and bounces his voice off a satellite into the space station's dry, recycled air.

"I have some bad news," Howell says, and because it's Howell who's delivering it, Pettit and Bowersox know exactly how bad before he gets it out: "We've lost the vehicle."

Nine words. That's all. Everything else is left unspoken, and in the quiet, the blanks are left for each of them to fill in on his own. In the way the parents of missing children hang on to the faintest hope that their loved ones are just lost, not lost for good, Pettit and Bowersox wonder whether any of Columbia's evacuation systems triggered, and whether any of their friends are floating down to a cloudless earth under parachutes.

Discovery of the crew's remains and a helmet on the grass later in the afternoon will push aside that faint hope for sadness.

The sadness will settle itself in.

Every so often on station, you're allowed to call home on the satellite phone, on closed channels, with the tape recorders turned off. These conversations keep you grounded. When no one is home—when it's time for her to get the groceries or for the kids to go to soccer practice—you have to leave a message on the machine: "Hey, honey, it's me, in space." Sometimes these messages are saved and listened to in the still of the night, again and again. Nowadays, these messages are almost always saved, because she never knows when they might become all she has left.

In that way, your family has finally caught up. You've learned already, over the course of your isolation training, after having been dropped into the winters of Cold Lake, Alberta, and left stranded in the woods, that the everyday interactions of life on earth—the messages left on machines, but also the smiles and waves from school buses and the notes left on fridges and pillows—are the things you need to carry. You make room for them in your memory's permanent collection, just as you learn to forget about the things that maybe you used to keep too close: what's on TV tonight, who's going to win the American League West. You come to understand the true order of things, because you know how the universe works. Some astronauts become the first men to walk on the moon, and others burn to death sitting on the launch pad, or seventy-three seconds after leaving it, or sixteen minutes from returning to it.

And sometimes you're no longer a month away from home—you're suddenly much farther, although you're not really sure how far, because the miles are meaningless. There are times when the space station orbits the earth less than 240 miles above its surface; there are moments when Dallas is farther away from Houston than you are.

What matters, what separates you from home, is time.

After the Columbia memorial service is piped in from the ground—after you hear President Bush say, "Their mission was almost complete, and we lost them so close to home," and you can't help thinking that they weren't very close at all—you ring the ship's bell, mounted on a bracket in Destiny, seven times for seven astronauts. The ringing still echoing in your ears, each of you finds a corner in which to try to come out the other side of your grief. A few of the things you usually do are left undone. In the meantime, your new reality begins to sink in: You remember Challenger, almost twenty years ago now, and you know, in your heart, that your ride home isn't coming anytime soon.

You tell Mission Control that you're all right, that you've trained a lifetime for this, that you can hold on to your memories for another year. Maybe longer if you have to. Part of you might even believe it.

The muscles in the legs always go first. On earth, they're kept twitching by fighting off gravity just enough to push out of bed. Without gravity, they begin to atrophy, and the body begins emptying out like another galley drawer. At the moment Columbia comes apart, Expedition Six has a month of experiments left to conduct. It also, at that moment, becomes one: The record for Americans in orbit is 196 days; another year in space would see Bowersox and Pettit eclipsing even the Russian records for being away.

Expedition Six has become the second kind of science in space. The first is programmatic science—studies that have been planned sometimes for years, experiments in fluid dynamics or crystal growth or protein production. The second, what Pettit, Bowersox, and Budarin are now, is fluke science—the science of accident.

None of them is a stranger to it. Pettit in particular fills his free time by opening random doors in the hallways of his imagination. When he gets too good at pushing back his coffee with chopsticks, he takes a sphere of water and blows on it, curious to see what wave pattern might result. (One that lasts ten minutes, turns out.) Or he injects air inside that same sphere with a syringe, and injects water inside that air, and watches the water bounce around inside itself until it becomes whole again, winning some small battle between mass and velocity. "Saturday-morning science," Bowersox calls it.

Mostly, though, they lose themselves in their routine again. Bowersox takes over most of the by-the-book work, donning an ugly tie whenever he needs a boost. He tends the plants, makes sure the crystals don't collapse in on themselves, monitors the instruments. It's his job, and close to a full-time one, to keep the station in orbit.

Pettit, with his official workload diminishing, conducts symphonies of his tiny, perfect spheres and begins to tinker. A button comes off his $3,000 NASA-issued wristwatch, and when he finds it wedged in a ventilator two weeks later, he decides to put it back in its place. He pulls his watch's guts out, sticks them to his worktable with double-sided tape, and finds a way to make them whole again—because Pettit believes everything can be fixed in time. Everything can be built to last.

He jogs on the treadmill and pedals the exercise bike for two hours each day, trying to stave off the inevitable decay. To keep the rest of themselves going, he, Bowersox, and Budarin make a point of having dinner together, of blasting a Santana record while they heat up their chicken fajitas—tortillas are good because they don't leave crumbs floating behind—Velcro their meal pouches and containers onto their foldout table, hook their legs around the restraint bars underneath it, and sit down to eat, like they did on earth, like the family they have become: Hey, honey, I'm home, in space.

There are those who dream of falling and those who dream of flying. Bowersox always dreamed of flying. He never knew why; he just knew that if he flapped his arms hard enough, he'd lift off the ground and glide over rooftops. It was in him and he went with it. Bowersox joined the Navy, became a fighter pilot, was assigned to Attack Squadron 22, logged more than three hundred arrested landings in A-7E's on the carrier USS Enterprise, and finally became a test pilot at China Lake, pushing F/A-18's to their limits. In 1987, he was selected by NASA as an astronaut candidate, underwent a year of training and evaluation, lost his ginger hair, and after a five-year wait, he earned his first zero-gravity trip. Now, with Expedition Six, and at forty-six years of age, built low to the ground and hard to tip over, he's gone into space five times—the record is seven—but even all those flights haven't put a rest to his dreaming. The only difference is now he doesn't have to flap his arms. All he needs to do is give a little kick and he can look down on skyscrapers.

Pettit operates on a different level. By schooling, he's a chemical engineer, and with his affinity for cargo pants and his perpetual bedhead, he looks it. But by inclination, he's an explorer, only more of science than of space. Fresh out of graduate school at the University of Arizona in 1984, he landed a job at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico. His project résumé was soon filled with things like this: "atmospheric spectroscopy measurements on noctilucent clouds seeded from sounding rocket payloads, volcano fumarole gas sampling on active volcanos, and problems in detonation physics applied to weapon systems."

He also filled up his garage after driving through a blizzard one night to an auction of surplus gear at the lab and finding himself alone in the seats. He bought everything he could stuff into his junky pickup, jury-rigged the power in his house to accept three-phase tools, and learned how to make liquid oxygen from scratch. NASA brought him onboard in 1996, not long after he'd turned forty-one but before he managed to blow himself up and cast a good chunk of the southwest into darkness.

He has since become a legend in Houston, tapped by his fellow astronauts to be the first man on Mars. The smart money began moving his way during his first weeks of astronaut training, when he raised his hand during a lecture on rocket propellants—namely, the liquid oxygen that was waiting to go off in his garage. "Do you know what color liquid oxygen is?" he asked the lecturer.

"Well, no," he replied. "I've never actually seen it. I'm not sure anyone has."

"It's blue," Pettit said from his seat at the back of the class. The rest of the students turned around to look at him. He looked back at them. "I just thought you'd be interested to know," he said.

Bowersox is the firstborn brother. He is reason and responsibility. Pettit, who has never before been in space, is the wide-eyed kid who eats his coffee with chopsticks.

Budarin is the weird uncle from Russia.

Somehow, it works—even if that, too, is an accident. Every year, NASA astronauts fill out "dream sheets," indicating what sort of mission they'd like, what's their ideal. And every year, Bowersox and Pettit would write, "I believe I'd be most effective on a long-duration mission," which was their way of begging to be sent to the space station. That shared desire was all the matchmaking they needed. From the start, they knew when to leave each other alone, when to blast Santana and do somersaults in the air. Even with the stress of their now open-ended mission, and their dwindling coffee supply, Pettit and Bowersox get along like old friends.

But they argue a few weeks after Columbia is lost. Someone has suggested that one of them might have to stay in space for a long time while the other is replaced by an incoming cosmonaut on a Russian rocket that would return the rescued man to earth. This proposal is known as the Avdeyev Option, named for Sergei Avdeyev, who also endured an unexpectedly long mission: He survived 379 consecutive days aboard Mir, the International Space Station's burned-up predecessor.

The problem is, both of them want to stay.

They've grown to like how their days unfold exactly as they want them to. They like never having to alter their routine to make room for someone else in it. They're never caught in traffic, bumped on the sidewalk, jostled on the subway, inconvenienced by the weather. They never have to take the car into the shop or shovel the driveway. They're never rushed. They're never late.

They've come to trust each other in ways they've never known before, the sort of unspoken trust that comes with the knowledge that one of you could take a hammer to a window and in fifteen seconds, the station and everything inside of it would pass into history. Once they found that, just about everything else fell into its one best place. Their lives are a strange kind of perfect, spotless and serene. Every day breaks with the promise of peace, and, with the exception of one Saturday in February, that promise is kept.

By March, approaching the start of month five in orbit, most of Expedition Six's to-do list has been exhausted. It's one of those rare, beautiful periods in his life when Pettit really has few demands on his time and nowhere else to be. So when he finishes building a gyroscope out of portable compact-disc players to hold his flashlight for him—because he can up here and he can't down there—he starts taking pictures, more than twenty-five thousand in all. First, he aims his over-the-counter Nikon at earth, waits for night to begin washing its way around the planet, and captures the physics of twilight, the strange hospital green that fills out the evening sky in thick, rolling waves. Then, after darkness has fallen, he looks for landmarks among the power grids and river bends, and he takes pictures of home.

At first, because the speed he's traveling is much faster than the snap of his camera's shutter, Pettit's pictures turn cities into streaks of white light, like the headlights in a time-lapse photo of a busy street. He takes clearer pictures when he learns to hold open the shutter and shift his shoulders in the opposite direction of his orbit, but even his best efforts turn out blurry; he knows he's looking at New York City, but he can't make out the black rectangle of lightless Central Park or the single bulb in the harbor that is the Statue of Liberty.

Not good enough. Pettit being Pettit, he puts together a makeshift, rotating tripod out of an old IMAX camera mount, a spare bolt, and a cordless Makita drill. Pressing the drill's trigger lends his camera the perfect rotation to take pictures sharp enough to make the miles meaningless all over again.

Looking at the electric webs that are Montreal or Tokyo or Washington, D. C., you can pick out the airports you've flown into and the streets you know and the hotels you've stayed in, and you can remember if the showers were hot or whether you ate a good meal there. In the end, if you close your eyes, you can even see your driveway, and you can feel yourself easing into it, throwing your junky pickup into park and walking up to the front door, your shoes scuffling on the asphalt, your hand guided by the warm light spilling out the windows to the door.

You have people waiting for you there.

All sorts of big days have come and gone. Birthdays, anniversaries, school concerts pass you by, even though you try to keep up. At Christmas, you make a cake with red icing. New Year's is harder to get a handle on; there are no crowds or fireworks, no clock strikes midnight.

Below you, SARS breaks out in Asia, Elizabeth Smart is found alive in Utah, the U. S. invades Iraq. March makes way for April. Now it's Opening Day. Who's going to win the American League West? It's just one more of sixteen dawns and dusks a day, just one more in an endless string of orbits.

Every so often, one of those orbits passes right over home, and your kids, because they're almost old enough to know what you know about the universe, wait on the front lawn to catch a glimpse of Dad. If the timing is right—if it's dark but the night is young enough for the sun to have dropped just below the horizon, still reflecting its rays off the space station's solar panels—they can strain their necks and spot a small, steady white light coming up over the trees. They'll follow that light with their eyes as long as it takes it to cross the starlit sky, on a smooth, predetermined path that'll be carrying it over Australia in less than forty-five minutes.

One of your boys, the youngest, always chases the light, taking off down the street, hoping to cover enough ground, enough of the curve of the earth, to earn even one more second in your line of sight. And always the light disappears.

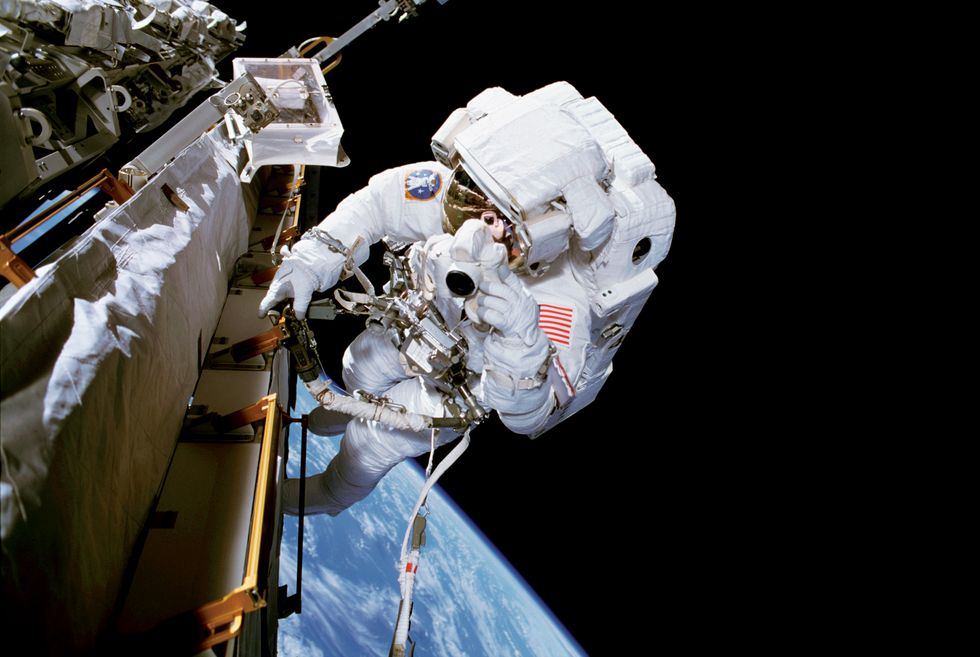

In the six years that it will take to finish stitching together the International Space Station, NASA has calculated, any single astronaut working outside its confines, connecting new modules or making repairs, will have a 1-in-800 chance of being struck by dust or a scrap of broken-down satellite. If he isn't killed by the impact, there's a greater-than-1-in-800 chance that the integrity of his space suit will be compromised and his blood will boil him to death.

Along with Opening Day, April has brought a sudden, more pressing gamble: the need to go outside. A thermal cover that protects the ammonia-filled fluid connector that helps the radiator systems cool things down—a "bootie," in astronaut vernacular—has worked loose, and with a 400 degree swing in temperature between the sun and the shade, it needs to be put back tight to limit the risk of overheating, rupture, and eventual combustion. This bootie is life.

Being the sort who pours himself into the job, Bowersox has been looking forward to the action. They walked in space once before, in January, and Bowersox hadn't wanted it to end—even after it almost didn't begin. After spending six hours wrestling into his diaper, water-cooled long underwear, and three-hundred-pound space suit, he'd struggled to open the goddamn hatch that would let him out. It had snagged on something—a piece of fabric from a strap that had come out of place, the sort of thing that on earth you'd pull away like lint but in space can "compromise the mission" and make men into satellites. Pettit, worried that Bowersox was going to break the hatch and turn their home into a vacuum, asked if he might take a swing at it. The hatch resisted him the way the driver-side door on his pickup always dug in, and he remembered, and he found his touch, and the hatch opened. The cloth tether connecting Bowersox and Pettit to each other was all that kept them from a good, strong push into eternity. And now here they are, staring into the pitch black again.

A fifty-five-foot length of steel cable is spooled near the hatch, a safety line and a leash all at once. Bowersox unhooks himself from the cloth tether and onto the cable. Next, he takes a breath, uses a handrail for leverage, swings his legs out into the emptiness, and looks down between his feet at the earth. That fifty-foot length of steel cable ties him to one of his worlds, and, in turn, to the other.

For the first time in months, Bowersox lets himself stall on that. He turns off the automatic pilot, and he takes it all in:

There's my feet. There's the earth. There's my feet, there's the earth, and there's a long way in between.

That's all the pause he gives himself, because there's work to be done.

Bowersox and Pettit have topped up their batteries and made certain that their nitrogen-thrust backpacks will fire if they need to move in a hurry, their one shot at returning to station if they lose their grip; they've run the inefficiencies out of their blood and triple-checked every rubber seal that separates them from the front pages; they've layered their gold-plated polycarbonate visors with antifog solution, but not so much that it might make their eyes sting. They've done a hundred little things to make it possible for them to do one more little thing, and they do that, too. After rerouting some power cables to one of the station's gyros, they pull the bootie back into place, keeping themselves in orbit for another day, and head back inside. They've been gone for almost seven hours. It feels, in a lot of ways, like coming home from a snowstorm, without having to stamp your boots.

In the airlock, they're coming down, exhausted, when Pettit catches the hint of a smell he can't place. It's come in with them, has embedded itself into the white fabric of their suits. It's metallic, but it's more than that. It's sweet and pleasant. It's the smell of space.

If something had gone wrong out there, had one of those rubber seals ruptured or a 1-in-800 long shot come through, it would've been the last piece of data for his brain to collect. He breathes it in again, then again. For some reason, the smell reminds him of summer.

And there it is.

During college, Pettit spent his vacations repairing heavy equipment for a small logging outfit in his native Oregon. He'd used an arc-welding torch to do it, and that torch had given off a sweet, pleasant, metallic smell.

Now here it is again. And now, for him, space smells like summer, the same summer that's greening the landscape below without him.

As the days pass, you can feel yourself changing. Not so much in the density of your bones or the fiber of your muscles—although those are deteriorating, you have already proved that, physically, men can last long enough to make it to Mars—but more in the wearing away of the calluses life has given you. It's as though all your skin has been stripped off and replaced with a fresh pink layer, except it runs deeper than that.

You decide to watch a movie. You've resisted until now, because there was always something better on outside your window, but sunrises and sunsets can get old after a few thousand ups and downs, and frankly, there just isn't much new to do anymore. Movie night it is. There are a bunch of DVDs on station—smuggled up over time—and IBM Think-Pads to gather around. On this night, the three of you decide to flip on Tank Girl, a cult hit among women astronauts, who have told you that if you do nothing else in space, you must watch this.

It might as well be playing in fast-forward. A man walks across broken glass, and the idea of it makes your fresh pink skin crawl. There are explosions that make you jump. There are nauseatingly bright colors and painful flashes of light; people shout too loud and fight too hard. There are tanks, and there are girls—luminous girls, with lips and breath and falling hair.

You look down at your hands, and they are shaking. Your mouth has gone dry. Your heart rate is galloping. Even after you've shut off the movie and pulled yourself into your sleeping bag, you tremble, like kids who've been told ghost stories around a campfire before lights-out.

Come morning, you've each drawn the same conclusion: Maybe you've been gone for too long. Maybe it's time to go home.

Because the earth has been spinning on its axis, and you've been spinning on yours, and now you know that you've been traveling in opposite directions for all this time, and you feel like you've never been so far away.

The voice coming out of the radio stops the drift. There is no Avdeyev Option. There will be no records set. Expedition Six is ordered to return. NASA has drawn out the decision, dreading the possibility of losing two more astronauts on a notoriously glitchy reentry vehicle. But if NASA waits any longer, the crew risks growing too weak to return on the only craft available.

Latched to the side of their ship is the Russian-built Soyuz TMA-1.

It's the same vehicle that was supposed to be former 'N Sync singer Lance Bass's ticket to ride back in October 2002, until he was found to be short on cash. The actual crew returned on another Soyuz, and the TMA-1 has been parked here since, just in case, like an escape pod straight out of science fiction, the bucket of bolts that somehow reaches hyperspace. Its chassis design is thirty-five years old: a greenish sphere with an insect's ass and two glass wings that pass for solar panels. Inside, the buttons are square and plastic. The onboard alphabet is Cyrillic. The cradles are made for small men, and the two portholes aren't much larger than dinner plates. But it's the only way home. And because a Soyuz's orbital life span is a little more than six months—the thing gets the hiccups if you look at it sideways, never mind bathing it in the universe's metallic exhaust—it's about that time.

So Pettit and Bowersox are about to become the first American astronauts to return home on a foreign vessel. They are also about to become the first American astronauts since 1975 to return home in a capsule, forced to put their faith in the parachute above them rather than in the landing gear below. They might have always dreamed of flying, but here, now, Expedition Six is being asked to fall.

They are also asked to begin packing up. It is the start of a monthlong goodbye, hard as any other. Because of the Soyuz's space and weight restrictions, the astronauts won't be able to bring home all the small things they brought up with them. There is room for only three personal effects, no more. The rest will be left up to memories.

This is most difficult for Pettit. Bowersox decides to take home his favorite pair of blue shorts, the same pair that Pettit had soaked with a wayward sphere of juice he was playing with at the dinner table, and a couple of golf shirts. The ugly tie stays. Easy, done. But Pettit is the only man in the seats at Los Alamos all over again, with only a single pocket on his low-profile white Russian space suit to fill.

He'll have to abandon his beloved tools, and, in the end, he decides to leave behind his wife's favorite necklace, which she'd dropped into his hands before he left and which he'd taken out and run through his fingers whenever he felt alone. He can buy her another one, he figures. And he can always buy new tools. What he can't replace are two long-handled spoons out of the galley, designed for digging the dregs out of the bottoms of pouches, with holes punched into their ends so they can be looped with idiot string and tied to his wrist, like mittens to a jacket. He hated those strings, so against regulations he cut them, but he fell in love with the spoons. Pettit thinks they're beautiful in their shape and utility. Perfect in their way. He'll give one to each of his two-year-old twin boys, and they'll take them along camping, eating whatever they heat up over the fire right out of the tin without ever touching the sides.

So there are the spoons, one, two. His chopsticks make three.

In an otherwise empty space behind the small-man cradles in the Soyuz TMA-1, there are soft-sided white bags that contain emergency supplies, including flares, warm clothes, water, and—because sometimes bad things happen—a double-barreled sawed-off shotgun. In the sixties, a Soyuz capsule landed off target, in rugged country, and after the cosmonauts inside had gathered their nerve, they broke open the hatch to find themselves surrounded by wolves, their breath turning solid in the cold. The men might have liked to run, but they could only crawl. Since then, every Soyuz crew packs a little something under the seat.

They don't carry much else in the way of insurance. The Soyuz's operation is almost fully automatic; it can't be controlled from the ground, and there's no override for the astronauts inside. They are, in the truest sense, passengers. After suiting up, climbing through a hatch, closing it behind them, and dropping into their formfitting seats—they lie on their backs, with their knees pulled up close to their chests—they go through a long checklist, and then they press a single button, once. That's it. For the almost four hours it will take them to get home, their fates are tied to one another and to the machine.

Bowersox, sitting in the left seat, with Budarin in the center and Pettit on the right, nods and presses that single button, exactly 160 days, twenty-one hours, and fifty minutes since they'd last felt gravity's pull. The undocking sequence begins. In their small diving bell of a capsule, sandwiched between the craft's two larger spheres—the living module and the propulsion module—a pair of monitors flickers to life in front of them. On the screens, they watch the station hatch they've just come through disappear, fast. They are folded into a vehicle with a volume of 141 cubic feet, a little more than the interior size of a Dodge Neon. They are traveling more than seventeen thousand miles per hour. Small rockets fire and drop them out of orbit, pushing them into the upper layers of the atmosphere. The weight of even the thinnest air begins to slow them down.

Their second round of separation follows. The living and propulsion modules have done their job, and they're ditched. Bowersox and Pettit each see one of the modules roll out past their windows and begin burning up.

They don't know that were everything in order, they wouldn't be able to see what they're seeing. They don't know that one of the rockets assigned to keep their own capsule stable has fired less than a second too late.

They don't know that until their monitors flash again.

The computers announce that they've pushed Expedition Six into a steep, ballistic descent. Instead of a gentle return to earth, they've entered an accelerated, lung-crunching dive into elementary physics. The hardware hasn't given them a choice: It's as if they've been loaded into their shotgun and fired straight into the earth.

The capsule begins to spin. There is sound and vibration, each rising in pitch. The view out their windows turns pink with plasma, then orange with flames. They learn what it feels like to ride inside a meteor. Things get warm. G forces build. Three to four to five to six. Seven to eight to nine, surpassing the limit that the body can survive for any length of time. Their teeth clench. Their spines compress. The weight of the world—more than a thousand pounds of it—sits on each of their chests. First it gets hard to talk. Then it gets hard to breathe. Russian ground control is oblivious. Everything in front of them indicates that all systems are normal. Bowersox, Pettit, and Budarin each feel their tongues getting pushed farther down their throats.

One final battle is being waged: gravity versus friction.

At last, the resistance of denser air begins winning out, slowing the capsule. They can feel the blood rising back to their faces, their tongues meeting their unclenching teeth.

Now the parachute. They are willing it to open. Bowersox begins to bristle at his lack of control. He wishes there were a big red button beside him that he could press, hard, to explode the sixteen pyrotechnic bolts that pin down the part of the capsule that holds the parachute tight. But there isn't. There's just the wait. Until, finally, what sounds like machine-gun fire echoes through the cabin, and the capsule shudders, and they feel the elastic tug of their lifelines pulled taut.

Above them, the massive orange-and-white parachute has filled out.

Below them, at Russia's Star City, where officials await the Soyuz's expected touchdown in sixteen minutes—how close to home Columbia was when it was lost for good—the radios crackle, then go dead.

In the silence, a few people put their faces into their hands. Everybody else looks white.

The heat shield strips away. The capsule vents, and the instruments get wet with condensation. There is vapor in the air. Through it and their windows, they can see the ground rising to meet them. Finally, six soft-landing rockets fire moments before impact, and the Soyuz lands upright with only a bit of a bump. Relief.

A moment later, the capsule begins bouncing across the flats, dragged along by the wind still filling the parachute. Budarin cuts it loose by pressing a button on a joystick that he wouldn't have wanted to press too soon. They come to rest on their sides, their arms hanging across their bodies, with Bowersox on the bottom of the pile. He looks out his window. All he can see is crushed grass, impossibly green. It has been that long since he's seen color unfiltered by space.

They figure they are going to land off tar-get, but not by much, so they stay strapped in, waiting for the helicopters to arrive. They are wrong, however; they have fallen north of the Aral Sea, in central Kazakhstan, far enough off target to be out of radio range, which is why Star City is in mourning. But that's something they don't know, even after they press a button to extend a blade-shaped radio antenna. Because the capsule is on its side, the antenna plunges straight into the ground, leaving them more removed from the outside world than they had ever been up there.

Time ticks by. They grow restless and stiff.

"I think we should get out," Bowersox says to Budarin.

"Yes," Budarin says. "I think we should get out."

There are no wolves. There are only white birds and blue sky and what turns out to be the Kazakhstan steppes, stretching out for almost three hundred empty miles between them and their target. There is a good possibility that in the history of the planet, no one has been there before.

But for them, now, it feels as familiar as breath itself. They drink up the air. In space, they'd been taking in a higher concentration of carbon dioxide than they were used to, and for Bowersox, it had left him feeling a little less than himself. Now, swallowing down great big gulps, he draws in a calm that he hasn't felt in a long time but had learned not to miss.

One by one, they fall to the ground. They try to walk, but they end up crawling, because their inner ears are still in space and standing up makes them feel sick. Budarin thinks he hears cars rolling in the distance and takes out the shotgun to fire off the flares. Bowersox goes back inside the blackened capsule and tries raising someone through the wash of radio static. Pettit decides that he can make a pretty nifty shelter out of the parachute. Bowersox then retrieves the emergency beacon from behind the seats and passes it out to Budarin, who flicks it on. A satellite orbiting the earth picks up the signal.

Soon, at Star City, there are celebrations, hugs and handshakes and pats on the back. For the technicians, at least, the last of the waiting is over.

After a couple of hours, one of fifteen search aircraft spots you. The fat-bellied military helicopters will follow. Together, you rest in the cool of the impossibly green grass, looking up at the white birds and, beyond them, the blue sky. You smile at the thought of holding your wife and your children, of feeling the rain, of sitting down to bottomless cups of fresh-brewed coffee without having to hunt for a straw. But you also savor the silence. You savor these last honest moments of being alone. And by the time the beat of the helicopter blades thumps over the horizon and the weight of the world has found your chest for the second time in the same afternoon, each of you lets your mind loose, floating, untethered, 240 miles up into the nothingness.

Each of you is dreaming of home.